The rise of the digital platform economy and urban mobility requires the reshaping of urban policy.

1. EU sustainability laws impose strict Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) obligations on multinationals, requiring thorough due diligence to detect occurrences of potential human rights abuses and climate impact throughout the supply chain. 2. Legal cases against companies such as BYD and Shell demonstrate rising risks of climate litigation and reputational damage globally. 3. Proposed incentives aim to achieve 90-percent reduction in Scope 3 emissions via contractual obligations and independent verification, ultimately leading to net-zero by 2050. |

In recent years, the social and environmental components of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) imperatives have had an increasingly significant impact on international supply chains, often leading to climate litigations, as well as reputational damages for the firms involved. In particular, as a result of the EU’s sustainability legislation – the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), the Forced Labour Regulation (FLR), the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the Directive on Empowering Consumers for the Green Transition (ECGT) – many of the largest multinationals, including non-EU entities, will be directly bound by these provisions. In addition, other entities, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) involved in EU-related supply chains, will be indirectly impacted by having to comply with contractually cascaded obligations.

To ensure compliance, and avoid potentially heavy fines and damage to their reputation, firms will have to implement climate targets, as well as incorporate sustainability-related obligations into their corporate business policies. They should not wait for EU sustainability legislation to come into effect, and must act now in their own best interest. In this article, I provide case examples, an overview of the CSDDD, and also recommend a proposal for governments to incentivise companies to achieve net-zero by 2050 through greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction.

REPUTATIONAL DAMAGE CAN HAVE FAR-REACHING EFFECTS

Within the last decade, there have been several cases that underline the importance for companies to establish and implement an effective and continuous sustainability/climate-related due diligence mechanism throughout their value chains – both upstream and downstream.

Take the case of Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer BYD. It is currently involved in a US$45.5-million lawsuit initiated by Brazilian authorities, who allege slavery-like conditions for more than 160 Chinese construction workers based at BYD’s factory construction project in Brazil. Although BYD issued a public statement stressing that it has zero tolerance for violations of human rights and labour laws, and holds its subcontractor responsible for the wrongdoing, the case was widely discussed in the media, resulting in very negative publicity for BYD.1,2,3,4

In another case, in 2019, Austrian stock exchange-listed chemical company Borealis AG (Borealis) commenced a €1-billion propane dehydrogenation plant construction project in Kallo, Belgium. In 2022, due to the intervention of Belgian authorities amid serious allegations concerning social fraud and human trafficking, Borealis was forced to halt the project for several months, contractually terminate contractors and re-tender major parts of the project, resulting in delays and major damage claims against the respective contractors.5

More recently, in May 2025, the Higher Regional Court of Hamm, Germany rendered a landmark decision in the case of the Peruvian farmer Saúl Luciano Lliuya against RWE, a multinational energy company headquartered in Germany. The plaintiff had alleged an increasing risk of melting glaciers that threatened to destroy his property, and said that RWE, as one of the world’s largest GHG emitters, should compensate him for investments to be made as protective measures and assume responsibility commensurate with its GHG emissions. The court corroborated that multinationals may be held directly liable for damages in connection with their GHG emissions.6 Although RWE’s share in worldwide GHG emissions would “only” be 0.24 percent and its share in global industrial emissions was recorded as 0.38 percent,7 it is striking that the court confirmed the materiality of RWE’s share. While this case was finally dismissed as the risk of the plaintiff’s property being destroyed was estimated as only one percent by expert witnesses, such climate change-related risk may be much higher in other locations as recently evidenced by the glacier collapse in Switzerland which devastated the village of Blatten.8 This decision may serve as a precedent for other courts to hold multinationals liable, surpassing the materiality threshold in relation to their contribution to worldwide GHG emissions.

In another case, this time against Royal Dutch Shell PLC (Shell), The Hague Court of Appeal in the Netherlands confirmed that social duty of care would imply that companies also have an obligation to contribute to climate change mitigation by reducing their Scope 1, 2, and 3 GHG emissions.9 The court stressed that more would be expected of Shell than of most other companies, given Shell’s major role in the fossil fuel market. However, the court clarified that Shell could not be ordered to achieve a certain reduction percentage (45 percent) by 2030 as demanded by the plaintiffs. Instead, Shell would be allowed to choose its own path to reduce its GHG emissions to achieve the climate targets laid down under the Paris Agreement and the European Climate Law. The case is currently pending in the Dutch Supreme Court.

CSDDD – EU’s KEY SUSTAINABILITY LEGISLATION

The most important and most disputed EU sustainability legislation is the CSDDD, which was passed in July 2024. EU member states were originally obliged to transpose the CSDDD into national law by July 26, 2026, with several transition periods that would end on July 26, 2029. However, in April 2025, the Council of the European Union (Council) and the European Parliament adopted the Stop-the-Clock Omnibus Directive to postpone the transposition by one year until July 26, 2027. Along with large EU companies (defined as those with a global net turnover of over €450 million from the previous year with over 1,000 employees), the CSDDD also directly covers all non-EU entities with an annual turnover within the EU surpassing €450 million. Prominent non-EU companies on this list include Amazon.com Inc, Apple Inc, COSCO Shipping Holdings Co., Ltd., McDonald’s Corp, China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation, The Walt Disney Company, BYD Co., Ltd., and Starbucks Corporation.10

The CSDDD requires companies to prevent the potential of, or bring to an end, actual environmental and human rights-related adverse impacts in relation to their own operations, as well as the operations of their subsidiaries and their chain of activities. This encapsulates all upstream supply chain tiers covering every indirect business partner including raw material providers, as well as downstream business partners related to the distribution, transport and storage of the respective products.

The risk-based due diligence approach of the CSDDD requires regulated entities to identify, assess, and prioritise adverse impacts, and also contractually cascade their codes of conduct containing the CSDDD-prescribed social and environmental obligations throughout the chain of activities. If necessary, this would include any prevention or corrective action plans, including remediation of injured stakeholders. Since the compliance with these codes and plans must be verified, the covered entities may use independent third-party verifiers like audit firms or rely on multi-stakeholder initiatives for such verifications. Audits of SMEs must be paid by the directly covered entities.

Contractual suspensions and terminations are a means of last resort in the event of severe potential or actual adverse impacts, and failed enhanced prevention/corrective action plans. Furthermore, the CSDDD contains an EU-wide civil liability regime and the possibility of administrative fines, whereas the maximum limit of such fines shall not be less than five percent of the net worldwide turnover of a covered company which violates its CSDDD obligations.

The CSDDD also requires companies within its scope to adopt and put into effect a climate-related transition plan to ensure, through their best efforts, that their business model and strategy are compatible with the climate targets stated in the Paris Agreement and the European Climate Law. The plan must also contain, where appropriate, absolute emission reduction targets for Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions. It is evident that value chain-related Scope 3 emission targets would be more appropriate for industries where the share of such emissions in the total GHG emissions is substantial, such as the oil and gas industry. For example, Shell’s share of Scope 3 emissions for its total GHG emissions is around 90 percent, making Shell’s Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions almost irrelevant. As Scope 3 emissions relate to the entire value chain of a company, they can realistically only be kept under control by means of contractually cascading GHG emission reduction obligations throughout the entire value chain.

Omnibus Directive Substantive Proposal

In February 2025, the European Commission adopted the Omnibus Directive Substantive Proposal to amend substantive parts of the CSDDD and the CSRD11, in order to simplify and streamline the sustainability legislation.

If the proposal is adopted by the Council and the European Parliament, in-depth assessments of indirect business partners throughout the chain of activities would only be required in the event of plausible information received by the regulated companies suggesting potential or actual adverse impacts. Sources of such information would include the whistleblower mechanism covering the entire chain of activities, which has to be established by every CSDDD-covered company; credible NGO (non-governmental organisation) or media reports; and independent third-party verifications of contractual assurances by direct and indirect business partners regarding their compliance with a regulated company’s code of conduct.

In addition, the EU-wide civil liability regime would be abolished, leaving affected stakeholders to rely on the national legislation of individual EU member states to access civil courts. This could encourage forum shopping, as such legislation exists in countries like France but not Germany. Nevertheless, the competent administrative authorities, on the basis of the CSDDD, would still have the competence to impose fines and grant remediation to injured natural and legal persons.

The obligation to put climate-related transition plans into effect would be removed, such that plans would only have to be adopted without any enforcement actions. However, the Omnibus Directive Substantive Proposal explicitly mentions “implementing actions” which can mean that although a transition plan would not have to be immediately implemented after its adoption, an adoption alone without any implementing actions would be deemed a violation of the CSDDD.

Finally, covered companies would no longer be mandated by the CSDDD to terminate contractual relationships in the case of severe adverse impacts, and failed enhanced prevention and corrective action plans. However, it is hard to imagine how, in practice, a CSDDD-covered company could remain in a contractual relationship if its enhanced corrective action plan fails in the event of severe adverse impacts such as child labour or groundwater poisoning.

In June 2025, the Council agreed on its negotiation position with regard to the Omnibus Directive Substantive Proposal. The European Parliament’s negotiation position is expected in October 2025. After that, long and difficult interinstitutional negotiations may further amend the proposal. The outcome is uncertain as it seems that the respective negotiation positions are far apart. It should also be noted that the Council’s negotiation position decisively waters down the climate-related transition plan by, among other things, replacing best efforts with a reasonable efforts obligation. If the European Parliament follows the recent decision of its Legal Affairs Committee,11a the European Parliament may be able to agree with the Council on its position on climate-related transition plans and the Council's intention to reduce the CSDDD's direct scope by extending the EU-wide net turnover threshold for non-EU entities to €1.5 billion and the worldwide net turnover threshold for EU entities to the same amount in addition to the requirement of 5,000 employees (instead of 1,000 employees) for EU entities. Nevertheless, many companies not surpassing these thresholds would still be indirectly impacted by means of the contractual cascading requirements which will remain untouched.

The US has been attempting to negotiate and remove the extraterritorial effect of the EU sustainability legislation. In August 2025, the Joint Statement on a US-EU framework based on reciprocal, fair and balanced trade was issued. It expressly stipulated that in the context of the CSDDD, the prevention of undue restrictions on transatlantic trade would include “undertaking efforts to reduce [the] administrative burden on businesses, including small- and medium-sized enterprises, and propose changes to the requirement for a harmonised civil liability regime for due diligence failures and to climate-transition-related obligations. The EU commits to work to address US concerns regarding the imposition of CSDDD requirements on companies of non-EU countries with relevant high-quality regulations.”12 In addition, a draft bill, the Prevent Regulatory Overreach from Turning Essential Companies into Targets Act of 2025, targets the CSDDD and other EU sustainability legislation by proposing that “no entity integral to the national interests of the US may comply with any foreign sustainability due diligence regulation.”13 It remains to be seen whether this bill will be enacted on a national level.

If the EU makes any concessions to the US in terms of the extraterritorial effect of the CSDDD, in particular by exempting US entities, it will immediately undermine the CSDDD’s credibility and effectiveness, as well as destroy the extraterritorial effect in its entirety. After all, why would other nations like China and India still comply if the US receives an exemption? Furthermore, a CSDDD exempting non-EU entities would lead to a severe competitive disadvantage for EU entities bound by the CSDDD.

Other countries are also raising their concerns about this legislation. A noteworthy example is Qatar, which recently threatened to stop its LNG (liquefied natural gas) supplies to the EU if the EU insists on Qatari companies being directly bound by the CSDDD.14

REALISTIC CHANCE OF ACHIEVING NET-ZERO

To realistically achieve net-zero by 2050, given that 157 of the largest multinationals jointly account for up to 60 percent of the global industrial GHG emissions,15 it is evident that such entities need to massively reduce their Scope 1, Scope 2, and in particular, their Scope 3 GHG emissions. Bearing this fact in mind, the following incentive- and reward-based mechanism directed at legislators across different jurisdictions is proposed.

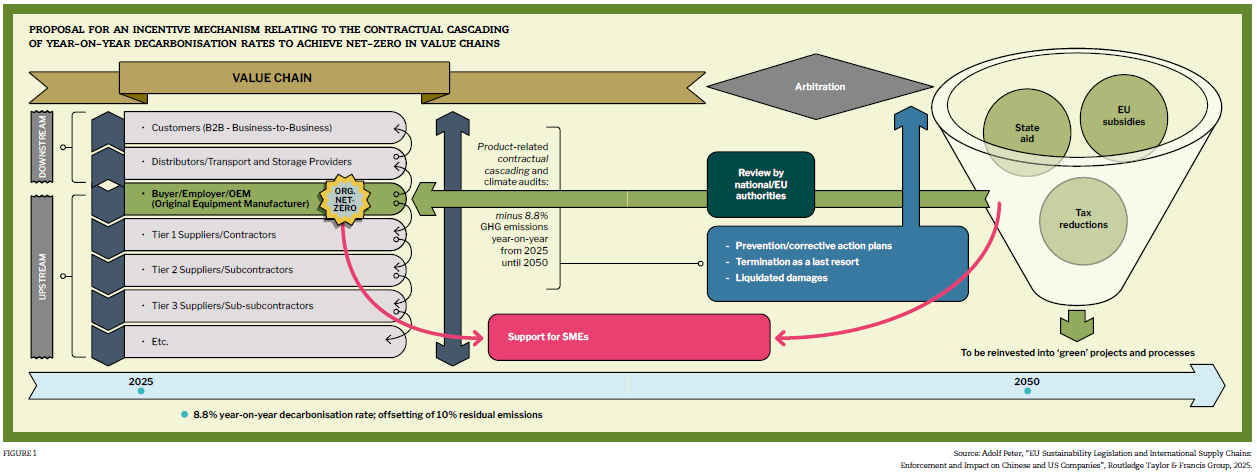

In stark contrast to existing climate-related EU funds or state aids that subsidise net-zero technologies resulting in GHG emission reductions,16 I propose subsidies and/or corporate tax reductions that cover an entire group of affiliated companies for organisational net-zero targets contractually enforced by annual year-on-year product/service-related GHG emission reduction targets covering entire value chains, which falls under Scope 3 (refer to Figure 1).

The subsidies and/or tax reductions should only be granted if the companies can meet the following requirements:

• Contractually cascade throughout their upstream and downstream value chain product/service-related year-on-year GHG emission reduction rates amounting to 8.8 percent (10-percent residual emissions to be offset if emission reductions start in 2025; the annual reduction percentage will increase if the contractual reduction mechanism commences later than 2025 while the target year stays the same) to achieve a total reduction of 90 percent in 2050.

• Annually verify the emission reductions by independent third parties on each value chain tier.

• Adopt and implement joint prevention action plans whenever it becomes clear that annual targets cannot be met.

• Adopt and implement joint corrective action plans in the event of failed annual targets.

• Actively support SMEs and value chain members from developing nations to achieve the annual product/service-related reduction targets.

• Enforce the achievement of the annual product- or service-related reduction targets by means of international commercial arbitration if prevention/corrective action plans fail, and terminate the respective contracts in the event of severe target failures.

• Introduce and implement a variable remuneration mechanism for the company’s management and directors which is dependent on the fulfilment of the annual product- and service-related reduction targets.

• Accept supervision and successfully pass annual assessments by competent administrative authorities in order to avoid greenwashing.

• Reinvest the received subsidies and/or tax reductions in other ‘green’ projects. The EU Taxonomy Regulation could be used for the determination of eligible ‘green’ investments.

An example of a company that has effectively employed climate clauses in value chains is Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL), a Chinese multinational. As the global leader of new energy innovative technologies, in particular batteries for electric vehicles, CATL employs a climate clause which assesses a product’s total GHG emissions; ensures the fulfilment of GHG emission reduction targets to achieve the contractually stipulated maximum GHG emissions; obliges contractual counterparts to use carbon offsets only for residual emissions’ neutralisation purposes; requires reviews by independent third parties with regard to the fulfilment of the GHG emission reduction targets; provides assistance to its business partners; and allows the termination of contracts – as a means of last resort – in the event of a failed annual GHG emission reduction target.17

LOOKING AHEAD

ESG-related issues can lead to significant damage, project standstills, re-tenders, and other business disruptions. Companies can avoid such pitfalls by establishing effective due diligence mechanisms. Thus, it is of utmost significance for companies to take this topic very seriously. To wait for EU sustainability legislation to finally become effective could be a crucial strategic mistake that could trigger major damages. 2026 will be a decisive year for the direction that the CSDDD (and other EU sustainability legislation) could take. However, even a watered-down CSDDD, in accordance with the European Commission’s proposal, would still remain the strictest sustainability-related due diligence legislation with extraterritorial effect worldwide.

Dr Adolf Peter

is Professor at Shanghai University of Political Science and Law

This article is based on his new book, “EU Sustainability Legislation and International Supply Chains. Enforcement and Impact on Chinese and US Entities”, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group London and New York, 2025

For a list of references to this article, please click here.