Private equity might provide higher returns, but investors should be aware of the associated risks.

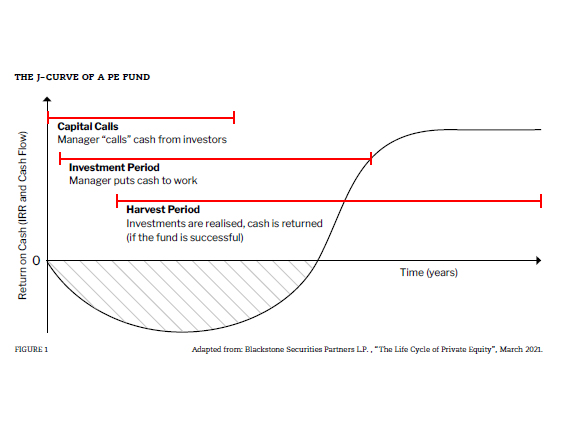

1. We provide a primer for investors and professionals exploring the possibility of tapping PE by tracing the evolution of this complex asset class from a niche investment strategy to a cornerstone of global finance. 2. There are three stages of PE funding, specifically early-stage, expansion, and maturity stages. PE firms create value at each stage through strategic guidance, operational improvements, and financial restructuring of portfolio companies. 3. We also look into PE fund structures, performance metrics, and the J-curve, noting that while PE can offer attractive long-term returns and portfolio diversification, achieving success requires a deep understanding of its complexities and careful due diligence before investing is carried out. |

Private equity (PE) often evokes images of high-stakes deals or legendary figures. Some associate it with the reality television show Shark Tank, where entrepreneurs have to convince investors (‘sharks’) of their business ideas. Others may remember The New York Times bestseller Barbarians at the Gate, which chronicles global investment firm KKR’s leveraged buyout (LBO) of the US conglomerate RJR Nabisco. In 1988, KKR executed what was then the largest LBO in history to take over the tobacco and food giant, which was valued at US$25 billion. The story was later adapted into a Hollywood film in 1993.

Over the decades, PE has evolved from a niche strategy to a cornerstone of global finance. It is not surprising that it has become one of the most significant alternative investment asset classes, attracting both seasoned investors and newcomers. By 2029, PE is projected to remain the largest private capital asset class, with assets under management (AUM) reaching approximately US$12 trillion.1

While media portrayals often highlight the glamour and excess of PE, the industry’s inner workings remain obscure to many. Beyond its mystique, this asset class plays a crucial role in driving economic growth and innovation, particularly in Asia where rapid development has created compelling opportunities in emerging markets.

Our article aims to unpack the complex world of PE, exploring its economic contributions, investment structures, performance metrics, and key differences from public markets.

WHAT IS PRIVATE EQUITY?

PE refers to investments in privately-held companies, i.e., firms not listed on public exchanges. Investors can acquire ownership stakes of these firms either directly or through PE funds. These investments are typically associated with higher return potential but involve trade-offs such as reduced liquidity, limited transparency, greater risk, and weaker regulatory oversight. What counts as PE can vary by region. In Europe, PE includes a broad range of privately financed equity investments, such as angel investments and venture capital (VC) in the early stage, growth capital in the expansion stage, and buyouts in the mature stage. In North America, however, PE more commonly refers to buyouts of mature private companies.

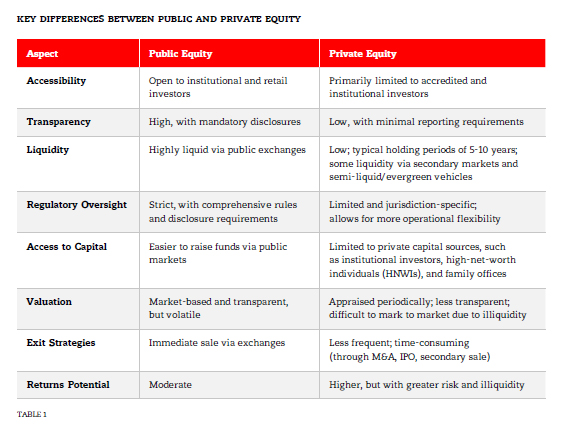

Compared to PE, public equity markets are accessible and transparent to both institutional and retail investors. Publicly traded companies are subject to stricter regulatory oversight, including mandatory and frequent financial disclosures. This ensures investors have access to timely and detailed financial information, protecting the interests of the broader investing public. PE, however, operates with fewer reporting requirements, offering less transparency to investors but greater flexibility for portfolio companies, i.e., companies owned by PE funds. Public equity markets benefit from receiving regular public disclosures, and having many market participants and intermediaries (e.g., traders and analysts), thereby allowing for efficient price discovery. In contrast, PE investors typically face limited access to information since private firms are not subject to the same disclosure requirements and information environment. Moreover, while public shares can be sold on exchanges, PE exit strategies or ways through which investors can convert ownership to cash are more restricted. PE exits are typically through sales to strategic buyers via mergers and acquisitions (M&A), to financial buyers, to another PE fund in secondary buyouts, or through initial public offerings (IPOs). These exits are not only less frequent, but also take longer to execute.

While the lack of liquidity and transparency poses challenges, these same characteristics also enable private firms to operate free from the pressure of short-term market expectations. With fewer reporting obligations, they can prioritise long-term strategy and value creation over short-term market demands or volatility, a key factor behind the growing appeal of PE. For risk-tolerant investors, this trade-off – accepting reduced liquidity and transparency in exchange for potentially higher returns – is at the heart of PE’s appeal (refer to Table 1 for the differences between public and private equity).

The aforementioned regulatory freedom, along with the potential for higher returns, has made PE increasingly attractive among certain types of investors. It has also contributed to a trend of companies remaining private for longer, or avoiding public listings entirely.2 Since the early 2000s, this shift is evident in the declining number of publicly listed companies in markets like the US and the UK. For example, the US saw a 43-percent decline in the number of public companies between 1996 and 2022, while listings on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) have declined by 42 percent from 2008 to 2023.3,4,5 This is because many firms have pursued take-private transactions or chosen not to go public, preferring the advantages of private capital. The appeal of PE is further supported by performance data. Bain & Company’s Asia-Pacific Private Equity Report 2024 found that PE outperformed public markets by four percent to six percent over 5-, 10-, and 20- year periods.6 The strength of these returns illustrates why PE has gained favour, particularly in Asia, where emerging market growth has created compelling investment opportunities.

Although there is no guarantee that PE will continue to outperform public markets, the number of private capital firms and the total AUM in private capital have steadily increased. The 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) in the US, enacted after the Enron and WorldCom scandals, also increased the relative attractiveness of PE over public equity. While SOX aimed to protect investors from fraudulent reporting by enhancing corporate governance, it inadvertently introduced significant compliance, audit, and reporting costs for publicly traded companies. These additional burdens encouraged many companies to go – or stay – private, contributing to a rise in take-private transactions, where a consortium of PE investors acquires a publicly listed company via a direct or leveraged buyout. These deals are especially popular during periods of low interest rates, which reduce borrowing costs.

Still, SOX is only one of the many factors behind the growing appeal of private markets. The broader surge in take-private activity over the past two decades has been driven by a confluence of factors including low interest rates, abundant private capital, and increased institutional investor interest in PE. This privatisation trend accelerated in the 2010s and early 2020s, as cheap debt financing enabled PE firms to fund large buyouts.

THE STAGES OF PE FUNDING

PE firms target different market segments and leverage specialised expertise to support the growth of their portfolio companies. Depending on the PE firm’s strategy, the focus may be on a specific industry, geographic region, or stage in a company’s lifecycle. The funding journey typically progresses through three key stages – early stage, expansion stage, and maturity stage – with each involving different types of investors.

Early-stage funding

At this early stage, small and emerging businesses (often start-ups leveraging new technologies) are typically unprofitable, lack established financial track records, and face a higher risk of failure. Consequently, they rarely rely on traditional debt financing, since lenders are generally more risk-averse than equity investors, especially when funding unproven ventures. Instead, founders with innovative ideas seek external capital to bring their concepts to market. With limited track records or inexperienced management teams, these entrepreneurs often begin by tapping into personal savings and raising informal funds from “family, friends, and fools” (FFF).

Angel and seed investors, as well as early-stage VCs, also play a key role during this phase. They provide funding by taking minority equity stakes and limiting the size of their investments to manage risk. Although these investments are inherently risky, they offer the potential for high returns and significant upside if the business succeeds.

Expansion stage

Once a business proves its viability, it may attract funding from late-stage VC and/or growth capital investors to scale operations and capture more market share. This marks the expansion stage, where companies seek capital to drive the next phase of growth.

A notable example of a successful VC-backed expansion is Grab Holdings. Initially launched as a ride-hailing platform connecting taxi drivers and passengers, Grab evolved into a super app offering services such as food delivery and digital payments.7 Over multiple funding rounds, VC and PE firms, including SoftBank’s Vision Fund and Vertex Venture Holdings, provided capital and strategic support to fuel Grab’s regional expansion and service diversification.8,9 In 2021, Grab was valued at approximately US$40 billion following its merger with Altimeter Growth Corp., a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) formed to take high-growth firms public through M&A.10

Maturity stage buyouts

Established and profitable companies often turn to PE buyout funds for capital to expand operations, improve efficiency, or enter new markets. These businesses, with proven business models and stable cash flows, typically carry lower risk than early-stage ventures.

Buyout funds usually acquire a controlling stake or full ownership, enabling them to improve efficiency and drive value creation through strategic, operational, and financial restructuring. These funds ultimately exit their investments through direct sales to strategic buyers via M&A, or financial buyers, IPOs, secondary buyouts, or recapitalisations.

A prominent Singapore example is the 2017 acquisition of Global Logistic Properties (GLP) by a consortium led by Hopu Investment and Hillhouse Capital in a US$11.6-billion deal. GLP, a Singapore-based logistics provider, managed a portfolio spanning 55 million square metres of space across major markets in China, Japan, the US, and Brazil. The acquisition strengthened the consortium’s leading position in the global supply chain infrastructure.11

VALUE CREATION

The PE industry plays a vital role in the economy by driving business growth, fostering innovation, and enhancing company performance. Through deep sector expertise and extensive networks, PE firms provide portfolio companies with strategic guidance, industry connections, business development support, and access to top-tier executive talent — factors that often strengthen management teams and operational execution.

Additionally, PE firms can stabilise distressed businesses by injecting capital and offering strategic oversight. However, employment outcomes following an acquisition may vary. Some firms experience growth and operational improvement, while others may undergo workforce reductions during restructuring. A 2019 study found that employment declined by 12 percent within two years of PE buyouts of publicly listed firms but increased by 15 percent following PE buyouts of privately held firms.12 These mixed outcomes reflect the balancing act that needs to be struck between operational efficiency and growth.

After acquiring control, PE firms typically focus on reducing inefficiencies and enhancing profitability. Leveraging deep industry expertise, they apply operational improvements, adopt advanced technologies, and integrate best practices to improve productivity. Financial restructuring may also occur, which may include refinancing debt under better terms, optimising working capital, and divesting non-core assets to sharpen strategic focus. While these actions can strengthen financial performance, they may also lead to job cuts, particularly in LBOs, where cost-cutting and asset stripping are more common.

Nevertheless, PE buyouts can accelerate ‘creative destruction’, a process where older jobs may disappear more rapidly but new roles emerge at a faster pace, ultimately leading to increased productivity. This dynamic highlights PE firms’ role in catalysing necessary economic adjustments, fostering innovation, and enhancing overall efficiency.13

Beyond financial and operational enhancements, PE firms play a crucial role in shaping competitive strategy. They may reposition companies to better align with evolving market opportunities, invest in new product development, and pursue innovation-driven growth.14 Once value creation initiatives are in place, PE firms aim to exit their investments under favourable market conditions. However, the success of these exits hinges on both market timing and the effectiveness of value creation efforts during the holding period. Market conditions, macroeconomic factors, and the firm’s ability to execute operational improvements all influence the final outcome.15

TRADITIONAL PE FUND INVESTMENT STRUCTURE

Large PE firms such as Blackstone, KKR, Carlyle, CVC, EQT, and Apollo manage large-scale transactions that demand substantial capital commitments. These investments support portfolio companies in scaling operations, entering new markets, developing innovative products, and enhancing strategic control.

To pursue diverse investment opportunities, PE firms launch multiple funds over time, each often targeting different geographies, sectors, or strategies. Finding good investment deals, also known as deal origination, is a critical capability. Leading PE firms maintain proprietary deal flow and cultivate strong networks with entrepreneurs, management teams, lawyers, investment bankers, and M&A advisors to ensure a steady pipeline of high-quality opportunities keep coming their way. Direct access to the entrepreneurs and senior management of target companies is a key success factor – one that provides a competitive edge in securing and winning deals.

Limited partnership structure

Most PE funds are structured as Limited Partnerships that are governed by a Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA). The General Partner (GP), also called the managing partner in some jurisdictions, acts as the fund manager, responsible for sourcing deals and managing investments. Limited Partners (LPs) are passive investors who provide the capital but do not engage in daily management. This model enables efficient allocation of capital, expertise, resources, and risks between fund managers and investors. The GP has full discretion over operational, financial, and strategic decisions for portfolio companies.

GPs typically raise capital through roadshows and private placements, pitching strategies to prospective LPs. Investors include institutional LPs like pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, foundations, funds of funds, and insurance companies, as well as accredited HNWIs and family offices. Due to the complexity and illiquidity of PE, individuals must meet strict qualifications to invest (e.g., Singapore’s Accredited Investor regime or Hong Kong’s Professional Investor criteria). Minimum individual commitments often start at US$250,000.16

Fee structure and incentive alignment

The classic principal-agent problem is present in many investment settings, including PE, where the GPs (agent) manage capital on behalf of the LPs (principal). There is a risk that GPs may not always act in the best interests of LPs, leading to potential misalignment of incentives and conflict of interests. To align interests and motivate long-term value creation, two primary fees are commonly charged by GPs.

The first is management fee. Typically fixed at around two percent per annum of committed capital, this fee supports the fund’s operating expenses, including staffing, administration, legal support, and sourcing. It is generally charged regardless of capital deployment, ensuring the fund’s continuous operation and deal execution capabilities. Some funds, however, base this fee on invested (rather than committed) capital, especially in later years.

The second kind of fee is performance fee, also known as ‘carried interest’ or ‘carry’. It is usually pegged at around 20 percent of profits exceeding a pre- agreed hurdle rate, which serves as a benchmark return considered acceptable for investors. The standard hurdle rate is typically around eight percent Internal Rate of Return (IRR), though it may range from seven to nine percent. (IRR is a time-weighted return that incorporates the timing and size of all cash flows. While widely used to compare investments, the IRR can be distorted by early large returns or short durations.) This ensures GPs are rewarded with performance fees only when investors earn above a hurdle rate, motivating GPs to prioritise long-term value creation over short-term gains and protecting LPs from paying fees on subpar returns. In many countries, particularly the US, carried interest is taxed as capital gains rather than ordinary income, thus allowing investors to benefit from lower tax rates. This preferential tax treatment is intended to encourage entrepreneurship and long-term risk-taking.

To further align their interests with LPs, GPs typically invest their own capital into the fund, usually holding a stake of between one and 10 percent – a practice known as having ‘skin in the game’. This commitment signals the GP’s confidence in the fund’s success.

Investment evaluation and performance metrics

Beyond leveraging connections, GPs actively source and evaluate deals through market research and conduct rigorous due diligence before making investment decisions. This process usually involves assessing the following aspects of the target company: business model and revenue drivers, the quality and track record of its management team, financial health and historical performance, industry outlook and market size, legal or regulatory risks, and alignment with fund strategy and time horizon.

Due to the varied nature of PE investments, assessing performance requires more than simple return calculations, and common metrics include IRR, as well as Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC) and Distributions to Paid-In Capital (DPI). MOIC represents the total value (realised and unrealised) divided by total invested capital, and gives a straightforward sense of capital growth – though it does not account for time. DPI measures how much cash has been returned to LPs relative to the amount they have paid into the fund (net of fees). A high DPI signals strong realised outcomes.

Together, these metrics offer a more complete picture of a fund’s efficiency, timing, and overall value delivery.

Fund lifecycle and the J-curve

Most traditional PE funds have a 10-year lifespan, often with two optional one-year extensions to allow flexibility in exiting investments under favourable conditions. They are structured as closed-end funds, meaning no new capital can be accepted once fundraising concludes. Investors commit a fixed capital amount upfront, which the GP calls upon in tranches as needed to fund acquisitions and operations of portfolio companies.

Capital calls or requests for committed funds from investors occur at irregular intervals, depending on deal flow. Uncalled capital – or ‘dry powder’ – remains committed but not yet invested. LPs must manage their liquidity carefully to meet capital calls that may arise with short notice. In the meantime, LPs often park uncalled capital in short-term, low-risk instruments to optimise returns until the funds are drawn down.

PE fund performance typically follows a J-curve trajectory (refer to Figure 1). In the early years, IRR and net cash flows are often negative due to fees, early-stage investments, and lack of exits. However, as portfolio companies mature, grow in value, and begin to be exited, cash flow distributions increase, and fund performance improves – often accelerating sharply in later years. The J-curve effect highlights the long-term nature of PE, and the patience required from investors seeking meaningful returns.

FINAL THOUGHTS

PE investments could offer the potential for attractive long-term returns and a meaningful source of portfolio diversification. But these benefits come with added complexity, opacity, and illiquidity. To succeed, investors must understand PE fund structures, valuation methodologies, fee arrangements, exit strategies, and market dynamics.

Those who invest the time to build knowledge and conduct thorough due diligence will be better equipped to assess whether PE aligns with their objectives. With a thoughtful and informed approach, PE can serve as a valuable addition to a diversified investment portfolio while managing its unique challenges.

Dr Yin Wang

is Assistant Professor of Accounting, Co-Director of MSc in Accounting (Data & Analytics) at the School of Accountancy, Singapore Management University

Steve Balaban, CFA

is Chief Investment Officer of Mink Capital, Chief Learning Officer of Mink Learning, and a lecturer at the University of Waterloo, Canada. He is also a contributing author on PE for the CFA Program

For a list of endnotes to this article, please click here.