The right approach depends on your organisation’s readiness.

1. Despite research supporting remote and hybrid work, many organisations, particularly those in Asia, are mandating a return to the office. 2. To navigate this shift, we propose a persona-based hybrid work framework that aligns employee needs with operational goals. 3. Our diagnostic model helps assess Work From Home (WFH) readiness, improve policy communication, and pilot context- specific strategies. |

The COVID-19 pandemic offered many lessons for humankind, chief among them was that work never stops. Despite being holed up in their homes, people continued to do their jobs. Meanwhile, WFH entered the workplace lexicon and has since become a topic of debate for corporate policymakers.

The prevalence of WFH has increased dramatically, rising nearly fivefold between 2019 and 2023,1 with approximately 40 percent of US employees working remotely at least one day per week.2 Recruiters in India note that over half of job applicants ask about remote work opportunities early in the hiring process.3 The need for totally remote or hybrid positions is evidently still increasing.

Research has shown that WFH has a clear upside.4 One of the leading experts on WFH policies, economist Nicholas Bloom of Stanford University, found that employees who work from home two days a week are just as productive as their fully office-based counterparts.5 A six-month study at a Chinese company, which is among the biggest online travel agencies in the world, found that its hybrid WFH policy enhanced job satisfaction and reduced quit rates by one-third, and performance evaluations over two subsequent years showed no negative impact.6 Writing about the advantages of remote work, Raj Choudhury, an associate professor at Harvard Business School, says work from anywhere boosts talent, productivity, and innovation.7 Employees like it too. The State of Remote Work report by social media management platform Buffer highlights key insights from 3,000 remote workers globally – 98 percent of respondents want to work remotely for the rest of their careers, and 91 percent report a positive experience working remotely.8 The top benefits are flexibility in time management, and the ability to choose one’s living and work locations.

However, despite substantive changes in information technology (IT) and remote working technology today, there has been a clear shift in employers’ preference back to working in the office. From Amazon and JP Morgan Chase to Grab and Wipro, companies across multiple industries have asked employees to Return to the Office (RTO),9 arguing that productivity suffers otherwise. This seems more prevalent in Asia – over 90 percent of firms in Hong Kong are urging their workers to increase their office presence, surpassing the global average of 56 percent.10 A recent University of Pittsburgh study on Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 corporations found that many managers have adopted RTO regulations to regain control over their workforce and make employees’ preference for WFH a scapegoat for bad firm performance.11

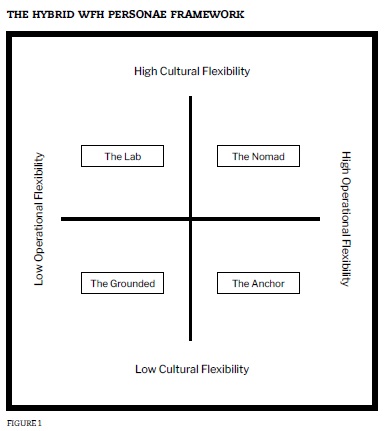

In this article, we examine how remote and hybrid work have become flashpoints in recent debates about productivity, culture, and control. First, we highlight the conflicting narratives around WFH in Asia, particularly the tension between employee preferences and leadership mandates. Then we introduce a two-axis framework, based on cultural flexibility and operational flexibility, that maps four organisational personae. This framework helps leaders assess where their organisations stand and how to modify their hybrid work strategies with greater intentionality.

THE EMPLOYEE- EMPLOYER PERCEPTION GAP: WHAT GIVES?

There is a notable divergence between employee and employer perspectives on remote work. While many employees report maintaining or increasing productivity when working from home, many employers remain sceptical. For instance, a survey by Microsoft revealed that 87 percent of employees felt they were as productive or more so when working remotely. However, 80 percent of managers disagreed, expressing concerns about decreased productivity in remote settings.12 If WFH is a win-win, why is there still a pushback from employers? More pertinently, should it even be a binary decision?

Employers’ reservations about remote work often centre on communication, collaboration, and organisational culture challenges. They are concerned about reduced supervision, and the potential decline in creativity and teamwork in remote work settings.13 Emerging evidence suggests that productivity outcomes also vary significantly according to the mode of working. While fully remote work is generally associated with a productivity decline of around 10 percent compared to entirely in-person work, hybrid models appear to maintain comparable productivity levels.14

The growing divergence between employee support for remote work and employer scepticism can be attributed to a few key reasons.

First, a significant perception gap exists between how employees and employers assess productivity. Employees tend to evaluate their performance based on task completion and efficiency gains from reduced commuting and fewer workplace interruptions. In contrast, managers often assess productivity through observable behaviours and process adherence – factors that are more difficult to monitor in remote settings. This gap has led to what Microsoft termed ‘productivity paranoia’, where 87 percent of remote employees reported being productive, yet only 12 percent of managers expressed confidence in that espoused productivity.15

Second, the erosion of managerial control in remote contexts contributes to organisational hesitancy. Traditional management practices are often rooted in direct oversight and face-to-face interaction, which are diminished in a virtual work environment. The lack of informal mentoring, spontaneous collaboration, and unstructured learning opportunities in fully remote settings has further fuelled concerns among employers.16

Third, remote work raises challenges for organisational culture and team cohesion. Research suggests in-person interaction is vital for cultivating shared norms, reinforcing organisational identity, and fostering trust among team members.17

Fourth, cognitive biases may influence employer attitudes. The status quo bias (a preference for established practices) and the availability heuristic (where isolated negative experiences in remote work are overemphasised) can skew managerial judgement.

Finally, a misalignment in performance evaluation metrics further explains this divergence. While employees often focus on task-level outputs, employers may emphasise broader key performance indicators (KPIs) such as innovation, cross-functional collaboration, and strategic alignment – dimensions perceived to suffer in remote environments due to limited informal interaction and collaborative spontaneity.18

HYBRID WFH PERSONAE FRAMEWORK

Interestingly, the largest percentage of people working from home is found in English-speaking nations, according to an April 2025 global survey of working arrangements carried out by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR).19 Another research report based on data from 34 countries corroborates these findings, reporting higher WFH rates in English-speaking countries (1.4 days) compared to Asia (0.7 days).20 In fact, the SIEPR report shows that Asian employees are more likely to work from home for half a day, whereas workers in Latin America and Africa typically log in at home once a week. That said, there may be notable differences within Asia. Countries like India and Singapore show a strong desire for remote work, whereas economies like China, South Korea, and Taiwan exhibit a more moderate preference.21 Culture is the one element that truly stands out. While Japan and the UK are comparable in terms of development, density, industrial mix, and lockdown duration, Japan had much lower levels of WFH than the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These differences have therefore sparked people’s widespread interest in trying to understand the dynamics of policymaking related to remote work. As firms adapt to post-pandemic realities, reconciling these divergent perspectives will be essential for designing sustainable and effective work arrangements. Various frameworks have emerged to help organisations navigate hybrid work transitions. These models typically fall into two broad categories: structural and employee-centric models. Structural models define hybrid work in terms of schedules and physical presence. An example is GitLab’s “Stages of Remote”, which outlines a progression from co-located to fully remote organisations, thereby emphasising operational maturity and cultural preparedness.22 In contrast, employee-centric models segment workers by preferences, behaviours, or life stages. For instance, Argyll’s hybrid personae (e.g., “Wellness Seekers” and “Maximisers”) categorise workers according to their motivational drivers, thus helping leaders to tailor office experiences.23

These models could lead to possibilities like a hybrid WFH policy, a logistical exercise, or a workforce preference map, whereas earlier models addressed different aspects of employer and employee criteria in isolation. Meanwhile, the framework below provides a comprehensive lens that serves as a diagnostic tool for policymaking at an organisational level.

INTRODUCING THE PERSONAE-BASED ORGANISATIONAL FRAMEWORK

Since 2020, when we first introduced the WFH personae framework in the article titled “Solving the Work-From-Home Conundrum” published in Asian Management Insights,24 the landscape of remote work has undergone a significant transformation. Initially, our framework aimed to assist organisations in developing actionable WFH policies that balanced employee well-being with productivity by categorising employees into distinct personae based on various dimensions.

In the years that followed, the rise of hybrid work models and the growing collection of empirical data have yielded deeper insights into the effectiveness of remote work arrangements. These developments have underscored the necessity to refine our framework to better align with contemporary organisational structures and employee expectations. Consequently, we have revised our original framework to incorporate new parameters such as organisational flexibility and operational flexibility. This updated model offers a more nuanced understanding of how companies can tailor their hybrid work strategies to accommodate diverse employee needs while maintaining operational effectiveness. The following sections will explore these enhancements, offering a thorough guide for organisations aiming to optimise their hybrid work policies in today’s dynamic work environment.

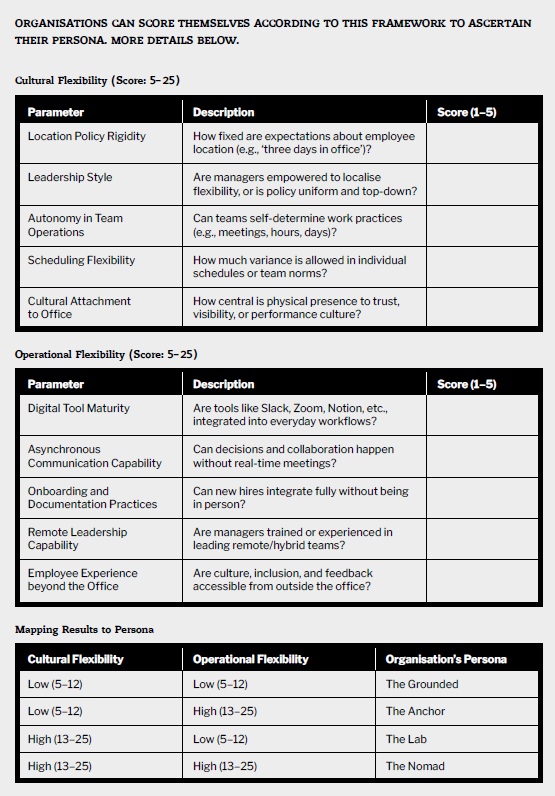

Our framework introduces a new lens that sees the organisation itself as a ‘person’. The parameters for this hybrid work personae framework have been chosen based on a synthesis of academic research and industry best practices that identify the key enablers and barriers of effective flexible work models (refer to Figure 1).

Working out the hybrid WFH personae framework

On the Cultural Flexibility axis, factors such as autonomy, location policy, and cultural attachment to the office reflect core findings in organisational behaviour literature, which emphasise the role of decentralised decision-making and employee control over work modalities in driving engagement and performance.25 Leadership style and scheduling norms further highlight how the extent of hybrid work success is influenced by policy, managerial interpretation, and cultural signals.26 This axis would measure how rigid or adaptive an organisation’s structures, policies, and leadership norms are regarding where and how work happens. Low Flexibility would imply top-down mandates, fixed schedules, and presence-focused culture, while High Flexibility would include factors such as role- or team-based autonomy, flexible scheduling, and trust-led norms.

The Operational Flexibility axis focuses on operational readiness for distributed work. It discusses how equipped an organisation is — technologically, operationally, and organisationally — for successful remote or hybrid work. Parameters like asynchronous capability, digital tooling, and remote onboarding practices are grounded in studies by Microsoft’s Work Trend Index,27 GitLab’s Remote Work Report,28 and research from Harvard Business School,29 all of which stress the importance of intentional systems and documentation for remote collaboration. Remote leadership capability and employee experience beyond the office, which are issues raised in Deloitte30 and McKinsey & Company31 reports, highlight the need to upskill leaders and build inclusive digital cultures as key differentiators for sustainable hybrid organisations. Low Enablement would be reflected by limited tooling, in-person default, and manager discomfort, while High Enablement would encompass factors such as asynchronous workflows, strong digital infrastructure, and distributed onboarding.

Unlike static scheduling models or individual worker taxonomies, this approach acknowledges that hybrid work is not just a policy but a strategic identity that is capable of evolving. It allows for blended personae, experimentation, and alignment between structure and strategy. Based on the above parameters, the four strategic archetypes are: The Grounded, The Anchor, The Lab, and The Nomad.

1. The Grounded: This is an organisation that values physical presence and structured environments, which is often driven by traditional leadership styles and legacy culture. It shows low cultural flexibility and limited maturity in supporting remote or hybrid models. The workplace is central to productivity, learning, and organisational control.

2. The Anchor:This is a technically mature organisation that possesses the tools and infrastructure for remote work but chooses to centralise work policies. It emphasises consistency, control, and standardisation over individual flexibility, and prioritises company-wide mandates over team-level autonomy.

3. The Lab: This is a transitional organisation experimenting with hybrid models. It is on the path to flexibility but is still navigating structural and cultural shifts. It exhibits moderate to high remote enablement maturity but has uneven adoption and variable support systems across teams or functions.

4. The Nomad: This is a remote-native or fully decentralised organisation with high flexibility and digital maturity. It thrives on asynchronous work, trust-based management, and fluid structures. It embraces employee autonomy and invests deeply in systems that enable distributed collaboration and belonging.

Personifying this framework

To further explain the use of this framework, examples of companies that fit into the grid are given below based on their cultural and operational policies.

1. The Grounded

Goldman Sachs exemplifies the Grounded persona as it is an office-centric organisation that is culturally attached to physical presence. Despite having the technological ability to support remote work, the leadership at Goldman Sachs strongly advocates for RTO, emphasising the importance of in-person collaboration, mentorship, and organisational cohesion.32 The firm’s insistence on a traditional workplace environment reflects low cultural flexibility and relatively low technical or operational maturity. This persona suits companies prioritising legacy culture, control, and visibility over flexibility.

2. The Anchor

IBM represents the Anchor – a company with high operational maturity but relatively low or rigid cultural flexibility. Although IBM was once a forerunner in remote work, it has reversed course and recalled many employees to the office.33 It retains robust digital infrastructure and systems that support remote collaboration, but its top-down policies and structured leadership approach limit team-level autonomy. This persona characterises organisations that can operate remotely but choose not to embrace decentralised work cultures fully.

3. The Lab

Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) is a strong example of the Lab persona. This archetype includes companies that are transitioning towards hybrid work with an experimental mindset. TCS’ vision of only 25 percent of its workforce needing to work from the office by 2025 reflects its ambition to embrace flexibility.34 However, it remains anchored in hierarchical structures and evolving cultural norms, resulting in uneven implementation across teams. The Lab persona is characterised by adaptability, pilot initiatives, and a willingness to learn and iterate, though it is not yet optimised for fully remote work.

4. The Nomad

GitLab is the quintessential Nomad, a remote-first organisation with high cultural flexibility and high operational maturity. From its inception, GitLab has built an all-remote culture, prioritising asynchronous workflows, extensive documentation, and employee autonomy. Its organisational model demonstrates how companies can thrive without physical offices by investing in digital infrastructure, trust, and transparent communication.35 The Nomad represents the leading edge of distributed work and is a blueprint for companies seeking to go fully remote without compromising performance or cohesion.

APPLYING THE FRAMEWORK

Employers can adopt this framework to aid effective WFH policymaking. This can help organisations communicate WFH policies more transparently to employees, reducing confusion and perceptions of unfairness. It also fosters leadership alignment across departments by creating a common language and decision-making framework. Such categorisation can also be used for experimentation, allowing employers to pilot one model in selected teams or functions, collect feedback systematically, and refine the approach before a full-scale rollout. To address these tensions, emerging organisational strategies should include adopting hybrid work models, investing in managerial training for remote leadership, and developing new productivity metrics better suited for distributed work.

Artificial intelligence (AI)-powered tools can further enhance this process by enabling real-time feedback collection, personalised communication at scale, and data-driven insights into employee engagement and productivity across different models. For example, AI chatbots can answer policy questions consistently, while natural language processing can help analyse employee sentiment from surveys or internal platforms, ensuring that both communication and policy adjustments are agile, inclusive, and responsive.

Remote arrangements offer compelling advantages, including substantial cost savings through reduced physical space requirements and access to a broader global talent pool. Hybrid work, in particular, has dual benefits – maintaining performance while enhancing employee recruitment and retention. As investment in technologies to improve virtual collaboration continues to grow, the WFH trend is expected to expand further, reflecting both a pandemic-induced inflection point and a sustained organisational culture and operational transformation in the world of work. This new framework will help managers make a more informed decision rather than adopt an all-or-nothing approach for WFH policies.

Dr Vineeta Dwivedi

is Associate Professor, Organisation and Leadership Studies, at S.P. Jain Institute of Management & Research

Dr Snehal Shah

is Professor, Organisation and Leadership Studies, at S.P. Jain Institute of Management & Research

For a list of endnotes to this article, please click here.