How the global e-commerce powerhouse harnessed artificial intelligence (AI) to balance innovation and intellectual property (IP) rights protection.

Alibaba, founded in 1999 by Jack Ma and his partners in Hangzhou, China, began as a business-to-business wholesale platform connecting local sellers to buyers abroad. That same year, it launched 1688.com, which became China’s largest domestic wholesale marketplace. Online shopping gained popularity rapidly during those dot-com boom days. In 2003, Alibaba introduced Taobao, a consumer-to-consumer platform, to counter eBay’s entry into China. After successfully overtaking eBay – dubbed the “shark in the ocean” by Ma – Alibaba expanded into other platform models. It launched Tmall, a business-to-consumer (B2C) marketplace in 2008, followed by AliExpress, a B2C platform for global buyers in 2010, and Tmall Global for international brands in 2014. In 2022, Alibaba had not only become a powerhouse in China’s digital economy but also the world’s largest e-commerce business in terms of gross merchandise value (GMV), which stood at an impressive US$1.3 trillion.1 The scale of the behemoth’s operations was a staggering 120 million active buyers with more than two billion products on its shopping platforms as of 2023.2

Over two decades, Alibaba has evolved into a multifaceted digital ecosystem beyond e-commerce, spanning logistics (Cainiao), cloud computing (Alibaba Cloud), digital media and entertainment (Youku), and other businesses such as healthcare and grocery retail. Its e-marketplaces offer convenience, global reach, and seamless trading, hence fuelling entrepreneurship in China while facilitating cross-border trade. However, this massive scale of millions of businesses and consumers across the globe also presents a double-edged sword. While e-marketplaces like Alibaba attract legitimate businesses, they also face challenges such as an influx of counterfeit goods from illegitimate sellers.

Globally, counterfeiting is a billion-dollar problem with counterfeit goods trading valued at US$467 billion in 2021.3 For international brands, counterfeiting undermines brand equity and leads to revenue loss. For consumers, it exposes them to low-quality or unsafe products, particularly pharmaceuticals and home electronics. For marketplaces like Alibaba, it erodes consumer trust, which is a cornerstone in e-commerce.

As the leading player in global e-commerce, Alibaba’s approach to the threat of counterfeiting is critical. Since formally establishing an IP protection mechanism in 2002, the company has faced pressures from domestic regulators, international brands, and consumers to do even more. Beginning from the mid-2010s, Alibaba started to move its IP governance approach from reactive enforcement to proactive IP rights protection by using AI-driven systems, brand and law enforcer partnerships, and institutional policy innovations. As of today, Alibaba’s IP governance model offers lessons for addressing some of the most complex challenges in counterfeiting by effectively leveraging technology, collaboration, and regulatory alignment.

EVOLUTION OF ALIBABA’S IP STRATEGY

Alibaba had been fighting an arduous battle against counterfeiting while implementing its IP protection regime. As a third-party marketplace, its lack of authority to validate sellers or authenticate products meant it had to depend on brand owners and consumers to report infringements, and rely on these parties to cooperate with law enforcers for IP dispute resolution. What made it more challenging was that some rights owners had refused to help during investigations, further complicating enforcement action.

Several key events would have prompted Alibaba to re-examine its IP strategy. Domestically, Alibaba had come under pressure from China’s former State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC). In 2015, SAIC, the country’s regulatory and enforcement authority, had released a white paper detailing widespread violations on Alibaba’s platforms but retracted it subsequently.

Internationally, foreign brands had accused Alibaba of not doing enough to stop the flooding of counterfeits on its platforms. Several frustrated American companies escalated complaints to the US government. That led to Taobao’s inclusion on the US Trade Representative’s Notorious Markets List in 2011, and again from 2016 to 2024. Alibaba responded by alleging that the inclusion was politically motivated and viewed itself as the scapegoat of US-China trade tensions.4

Legal battles followed. In 2015, Kering Group – the French owner of luxury brands Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent – sued Alibaba for facilitating the sale of counterfeit goods, citing US$2 fake Gucci bags on the latter’s platforms.5 Alibaba dismissed the claims, stating they were baseless. However, after two years of negotiations, Alibaba and Kering jointly announced a new partnership to combat counterfeiting. Intensified scrutiny at home and abroad threatened Alibaba’s global reputation and would have escalated pressures to shift towards a more comprehensive and sophisticated IP governance approach.

In the early years of IP governance, Alibaba relied heavily on rights holders to report infringements, followed by a manually tedious process of verifying and taking the offending listings down. Launched in 2002, its first IP complaint system handled take-down requests via email. Dedicated platforms like AliProtect and TaoProtect were set up in 2008 and 2011 respectively, allowing brand owners to register their IP rights, submit complaints online, and await Alibaba’s final decision on the removal of counterfeit product listings.

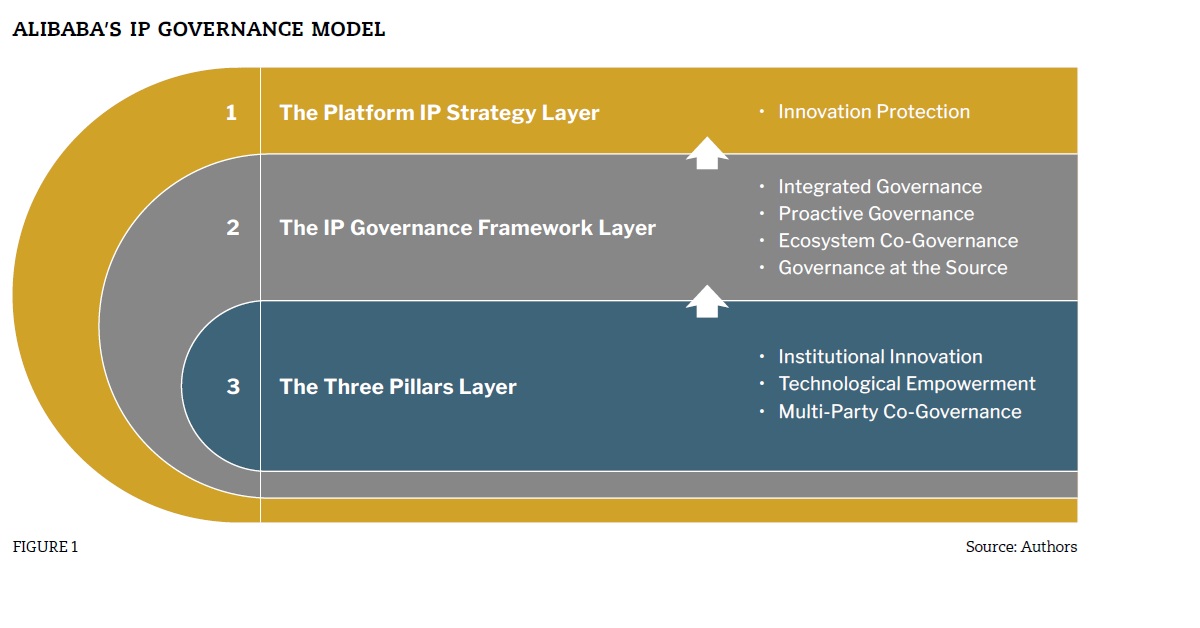

Building on earlier initiatives, Alibaba’s governance model gradually matured into a multi-pronged framework comprising integrated governance via the IP Protection Platform, proactive governance enabled by cutting-edge technologies, ecosystem co-governance through online-offline collaboration, and governance at the source in the form of crackdowns. Three main pillars – institutional innovation, technology empowerment, and multi-party co-governance – drove these creative governance measures.

INSTITUTIONAL INNOVATION

In late 2015, Alibaba set up its Platform Governance Department. The internal watchdog unit was tasked not only with enforcing IP-related rules across its online shopping platforms, but also safeguarding IP rights and setting standards for product safety and quality. As a result of institutionalising this responsibility, Alibaba made clear how it was committed to making IP protection a key component of its platform governance and business strategy.

Next, Alibaba launched measures to build a culture of greater accountability by rewarding responsible merchants while disciplining repeat offenders. The same year, Alibaba initiated the Good Faith Program to spur continual responsible engagement from brand owners with a proven track record of correct counterfeit reporting. Alibaba would speed up the review and takedown process for these rights holders by shortening the time needed from six to two working days. Simultaneously, Alibaba implemented the “Three Strikes and You’re Out” penalty system to prevent errant sellers from breaking the rules. A warning would be given after the first breach (or ‘strike’), followed by a one-week listing interruption after the second, and finally, account closure after the third.

In the beginning, Alibaba’s IP protection measures concentrated on important brands with registered patents, copyrights, and trademarks. In 2018, the company expanded the coverage to include small business owners that had introduced their novel products on Taobao or Tmall. Under the Original Design Protection Program, small-scale innovators enjoyed similar protection to that of right-holders of major brands without undergoing expensive and time-consuming IP registration procedures. Large enterprises also benefitted from this programme, often leveraging it together with formal IP rights to strengthen the protection of their innovations. This initiative marked a milestone in Alibaba’s efforts to protect start-up entrepreneurs who faced challenges from counterfeiters replicating and selling imitations of original designs.

An example of such an entrepreneur was Shen Wenjiao, a China-based designer of the award-winning NUDE coat stand. Despite holding the design patent of the hugely popular coat stand, which took over two years to conceptualise, his company could not secure judicial protection to safeguard the innovation. Widespread counterfeiting and dismal sales eventually led the company to chalk up heavy debts and declare bankruptcy in 2017. Shen’s case led Alibaba’s Platform Governance Department to establish the Original Design Protection Program – an initiative that helps small businesses fight against counterfeiting and earn a fair profit from their innovations.

TECHNOLOGICAL ENABLEMENT

To enable brand owners to better manage their IP rights, Alibaba merged AliProtect and TaoProtect into a single portal named the IP Protection (IPP) Platform in 2016. In addition, participating brands were assigned a dedicated account manager to help them resolve complex disputes. In the following year, the launch of Express IPP further empowered brands through advanced data modelling for quick processing and takedown of reported counterfeit listings within 24 hours.

While the IPP Platform served its purposes, manual enforcement became unsustainable due to the rapid expansion of e-commerce and along with it, the growing scale of counterfeiting. From 2013 to 2014, Alibaba invested US$161 million in state-of-the-art technologies to address counterfeiting.6 This move signalled a shift towards a proactive approach to IP governance, in which pre-empting IP violations, rather than reacting to them, was key.

Underpinning Alibaba’s proactive governance was the deployment of cutting-edge technologies. At the heart of the IPP Platform is the powerful “IP Rights Protection Tech Brain” – a suite of proprietary and patented technologies comprising AI-powered tools built on deep learning capabilities, data mining, blockchain, biometric technology, image recognition and semantic recognition algorithms, as well as cloud computing. Leveraging a combination of the above technologies, the IPP Platform can automatically scan millions of product listings, recognise subtle differences in images, identify unusual keyword patterns, detect abnormal seller behaviour, and remove potential IP rights infringement – all in real time.

By comparing suspected logos with a mega database containing over a million trademarks from 500 luxury brands and billions of sample product images, the system can determine authenticity in under 50 milliseconds, nearly twice as fast as the blinking of an eye.7 With a high degree of accuracy, 96 percent of suspicious products can be promptly identified, intercepted, and removed the moment they are listed and before they are even sold to consumers.8

Predictive algorithms are also utilised in the detection and reduction of ‘false negative’ complaints filed by companies making false allegations against legitimate stores. These sabotaging complaints account for nearly one-quarter of all IP complaints, affecting around one million brands and causing them to incur an estimated loss of US$16 million in 2016 alone.9

Alibaba’s technological empowerment approach entails embedding AI, big data, and other cutting-edge technologies into almost every layer of its enforcement infrastructure.

MULTI-PARTY CO-GOVERNANCE

Recognising that no single company could win the war against counterfeiting alone, Alibaba built a robust IP regime based on the collaborative effort of multiple stakeholders, including industry coalitions and law enforcement agencies.

Deciding that it was crucial to demolish counterfeit production at its source, Alibaba set up an anti-counterfeiting task force dedicated to combatting offline IP infringements in 2016. Alibaba also established the Cloud Sword Alliance, collaborating with local provincial law enforcement agencies to identify counterfeit manufacturing facilities and assist them in conducting timely crackdowns. As an added deterrence, Alibaba also initiated lawsuits against counterfeiters, including China’s first e-commerce civil litigation against sellers of counterfeit Swarovski watches in 2017, as well as joint lawsuits with brands such as Kweichow Moutai, Erdos Cashmere Group, and Peacebird Fashion International.

Separately, in 2017, Alibaba launched the Alibaba Anti-Counterfeiting Alliance (AACA), a network of law enforcement agencies, rights holders, and industry players that jointly committed to IP governance. The AACA comprised over 220 organisation members from Europe, North America, Asia Pacific, and China, representing more than 1,100 brands such as Apple, Chanel, and 3M as of 2022.10 In its 2022 IP protection report, Alibaba stated that it had used laws and regulations from around the world as a benchmark to develop sound, transparent, and fair IP rules for its platforms.11

The following year, AACA introduced the Queqiao Project, a programme to monitor the infringement of IP rights. The name “Queqiao” means “magpie bridge” in Chinese, symbolising the mythical bridge that connects brands with Alibaba’s platforms in the fight against counterfeiting. Through Queqiao, members cooperate on counterfeit discovery, with the help of Alibaba’s sophisticated tools like a digital dashboard that helps them to spot copyright infringements cost- effectively and begin one-click take-downs effortlessly.

To augment its ability to uncover rights violations, Alibaba tapped machine learning algorithms to arm Queqiao with sophisticated infringement detection tools. Among them were invisible watermarks embedded in images and documents that demonstrate brand ownership, user behaviour analysis to mark questionable activities, and optical character recognition to digitise printed text, which would make document scanning easier.

Besides enforcement, AACA also offered IP protection education to rights holders and the public by holding IP law seminars. Such training tackled issues like IP violations, trademark misappropriation, and copyright abuse, hence building a stronger awareness and understanding of the importance of why IP protection is crucial.

Additionally, Alibaba worked to enhance its global trustworthiness by becoming a member of the International Anti-Counterfeiting Coalition (IACC) in 2016, and was the first e-commerce platform to join this body. While this move initially drew criticism leading to a suspension, Alibaba upheld its dedication to fight counterfeiting, showing that 110,000 fake listings had been taken down from its platforms and US$125.5 million worth of counterfeit goods were seized in 2015 alone.12 The success of these efforts had hugely surpassed that of the previous three decades combined.

THE ROAD AHEAD

Since formally implementing its first IP protection mechanism two decades ago, Alibaba has made big strides in executing its multi-pronged IP strategy and delivered considerable results. The Chinese e-commerce giant has positioned itself as the leader in IP governance in the global digital marketplace and set the precedent for other platforms struggling with anti-counterfeiting challenges. Alibaba has redefined the role of an e-commerce platform – from a passive intermediary taking down counterfeit listings to a proactive platform maintaining oversight of product quality and consumer trust.

By 2024, its challenges have nevertheless persisted. Counterfeiters have become increasingly adept at circumventing automated detection systems. They utilise sophisticated tactics to promote their products, such as posting decoy listings with hidden links that direct consumers to external websites selling fake goods. Alibaba also had to confront the competing priorities of major brands and small-time sellers on its platforms. While the company has tightened enforcement for the benefit of international brands and consumers, at the same time, it has served millions of small businesses domestically on Taobao and Tmall, which contributed to more than two-thirds of the company’s total revenue.

While Alibaba’s IP protection system is robust, its effectiveness is limited to its ecosystem and cannot address cross-platform infringements such as counterfeiters reselling imitation goods on other platforms. Addressing this limitation would require collaboration among multiple e-commerce platforms, which remains challenging due to different IP strategies and policies adopted by each platform.

The road ahead for Alibaba lies not only in significantly reducing the prevalence of counterfeits in its e-marketplaces, since completely eradicating counterfeiting appears impossible, but also in writing the next chapter on global IP protection. As its e-marketplaces continue to grow in scale and complexity, the long-term imperative would be to build a safer, more transparent ecosystem, not only in China, but worldwide.

Dr Liang Chen

is Associate Professor of Strategy & Entrepreneurship and Lee Kong Chian Fellow at Lee Kong Chian School of Business, Singapore Management University

Dr Cheah Sin Mei

is Assistant Director at the Centre for Management Practice at Singapore Management University

Dr Can Huang

is Professor, Associate Dean, Director of Zhejiang Provincial Data Intellectual Property Research Center, Executive Deputy Director of National Institute for Innovation Management, and Co-Director of Institute for Intellectual Property Management at School of Management, Zhejiang University

Guoqiao Liu

is a doctoral student at School of Management, Zhejiang University

This article is based on the case study ‘Alibaba’s Innovation-Driven Approach to Intellectual Property Rights Governance’ published by the Centre for Management Practice at Singapore Management University. For more information, please please click here.

For a list of references and additional readings accompanying this article, please click here.